Two months.

That is how long Anthony Burns had tasted freedom in Boston before his enslaver, Charles Suttle, came to Boston to reclaim “his property.”

In 1854, when Charles Suttle came to recapture Anthony Burns many of the people of that time (and sadly many in our current time) may have said Suttle was a “good master” as Burns enjoyed privileges that many other enslaved persons others did not.1 Burns could read and write. He was loaned out to others and was able to make money for himself so long as his enslaver received a cut. Even so, those privileges did not spare Burns from the whip nor prevent him from being injured in his indentured servitude.

But the fiction of the the “good master” can be dispelled immediately for no man who holds another in bondage can also be good. No man who denies his fellow man their autonomy can be good. No man who demands to be called master can also wish to be called good.

Privileges or not, Burns desired Freedom. The chance to live his own life, accountable to himself an no one else. A Freedom from privileged bondage. A Freedom that he would never have under the yoke of Charles Suttle. That desire for Freedom is what pushed Anthony Burns to stowaway on a ship headed to Boston in February of 1854.

When Burns arrived in Boston, sometime in late February or early March. he stepped off the ship that had carried him and on to the land, a free man. A fugitive yes, but free. Free from his daily checkins with Suttle. Free from paying his enslaver a cut of his wages. Free to succeed or fail on his own terms.

However, Suttle wasn’t done with Burns as he chased Burns up to Boston and bring him back to Virginia. Suttle would sieze and restore his property, Freedom be damned.

Charles Suttle had an ally in his hunt for the escaped enslaved person. The United States Government, thanks to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850.

Enslavers had always been able to chase their escaped enslaved persons into states and territories that did not recognize or had outlawed slavery. The ability to do so goes back to the original Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which itself was an enforcement mechanism of Article 4, Section 2, Clause 3 of the US Constution, which said:

“No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due.” 2

The 1793 Act allowed enslavers to enter a free state or terrtory that their escaped enslave person had fled to, arrest and recapture them, and then present them to a judge with proof the enslaved person was their “property” and should be returned to bondage. This Act would also fine any who aided and abetted the escaped person with a fine of $500 for hindering their recapture by their enslaver.3

However, by 1850, much had changed in America. Anti-slavery sentiment had grown, particularly in Northern states. More and more, the people held in bondage by their enslavers risked a flight for Freedom to the North; and more and more, upon arriving, they were assissted in that escape. Abolitionists, free Black men and women, churches and prominent prolitical figures would harbor these self-emancipated people. Help them find employment. Assist them in their journeys to Canada or England, where the enslavers cruel arms could not reach.

The resistance against slavery had grown in the North to such a point that by 1850, nine states had passed Liberty Laws with the intent of restricting enslavers from siezing their escaped persons and taking them back to forced labor camps of the South. People within those Free states decided collectively and individually, that it didn’t matter if the law gave men the power to detain, and dehumanize their fellow man, they were unjust and needed to be fought at every step.

Southerners and enslavers alike howled at these Liberty Laws, stating they were unconstitutional. That the Northern states had violated federal law. The enslavers and their enablers were stymied in their unjust pursuit of self-emancipated men and women. The enslavers were so angry at the Free states that if wouldn’t help them willingly in their their cruel endeavors, Congress would force the issue.

This brings us to the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, passed by the Thirty-First Congress, and signed into law by President Millard Fillmore, took the enforcement provisions of the 1793 Act and made them even more stringent. 4 Now, not only was an enslaver allowed to pursue his escaped person into Free states, he was able to use Federal power to do so. Judges and and Marshalls were required to issue warrants for the arrest and capture of newly free men and women. Refuse to recapture these people? Fines would be issued of $1,000 to those marshalls that didn’t want to be a part of the forced bondage of their fellow man.

And if you were a private citizen, one who saw the evil of slavery and wanted to assist in enslaved persons realizing their freedom regardless of what the law said, whether that assistance was simply providing them a hot meal, or a place to sleep, or aid to the next stop to Freedom? That person would not only be fined a thousand dollars for the act of defiance, but another thousand for each enslaved person they assisted in escape as well as six months of jail. All for doing the right and just action.

That any person who shall knowingly and willingly obstruct, hinder, or prevent such claimant, his agent or attorney, or any person or persons lawfully assisting him, her, or them, from arresting such a fugitive from service or labor… or shall aid, abet, or assist such person so owing service or labor as aforesaid, directly or indirectly, to escape from such claimant … shall, for either of said offences, be subject to a fine not exceeding one thousand dollars, and imprisonment not exceeding six months … and shall moreover forfeit and pay, by way of civil damages to the party injured by such illegal conduct, the sum of one thousand dollars for each fugitive so lost as aforesaid, to be recovered by action of debt, in any of the District or Territorial Courts aforesaid, within whose jurisdiction the said offence may have been committed.5

What made the Fugitive Slave Act so base and wrong, so meticulously evil, was that it made the act of compassion illegal. It punished those that saw the deprivations of Slavery, those that wanted to end it, those that wanted all to be free under the law. It told American citizens that if they assist in the aid to Freedom, they would be jailed. It told Americans that if they provided aid or comfort to those yearning to be free, they themselves would have their lives destroyed.

Which brings us back to Anthony Burns.

On May 24, Anthony Burns was arrested while walking the streets of Boston. A warrant was issued for Burns’ arrest at the behest of Charles Suttle, and fugitive slave catcher Asa Butman, saw Burns on the streets of Boston and arrested him, taking him to the to the courthouse to await “trial” though it should be noted that the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act also prevented Burns from speaking in his own defense as “in no trial or hearing under this act shalled the testimony of such alleged figutive be admitted in evidence.“6

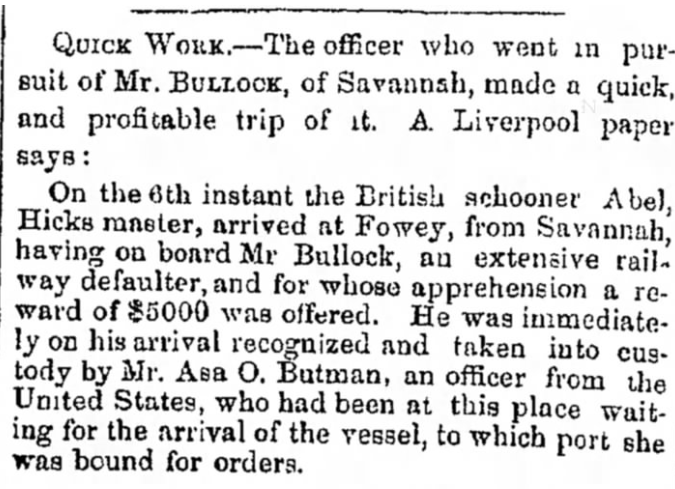

For Butman’s part, he not only gleefully executed the warrant as a marshall of the United States, but he often profited from it. In one such recapture, he chased a man to England, collecting a $5,000 reward for his his efforts. 7

Asa Butman wasn’t just “following orders.” He was a complicit and more than willing participant.

On May 26, as Anthony Burns sat in in the courthouse awaiting trial, a group of abolitionists formed and set upon the courthouse, determined to free Burns.

“’There [they] proceeded with a long plank, which they used as a battering-ram, and two axes to break in and force an entrance,’ one report described in detail. Soon ‘pistols were heard in the crowd’ and ‘some thirty shots were fired by rioters.’ Their attempt was ultimately unsuccessful, however, with the event ending in the death of a federal marshal and the arrests of 13 people.”8

After the riot to free Burns, he was convicted and remanded to his enslaver’s custody where he was sold off to another enslaver. Before he was taken from Boston, President Franklin Pierce, an avid supporter of the Fugitive Slave Act sent in hundreds of troops to Boston, to quell any unrest and ensure that Charles Suttle could safely take his “property” back to Virgina. What a scene that must have been, the United States military used against its own people to ensure the enslavement and bondage of their fellow man.

Though the abolitionists lost the battle the night of May 26 to free Burns, they did not give up the war. Leonard Grimes, a Black Baptist preacher at the Twelfth Baptist Church in Boston championed Burns’ cause.9 For years, Grimes was a man who aided those seeking to be Free, often risking and suffering imprisonment himself, his with his pews at his church in Boston full of the self-emancipated; he fought against the Fugitive Act with the same vigor as the vile Asa Butman did to enforce it. Grimes, among other supporters of Abolition in general, and Burns in particular, were able to raise $1200 and purchase back his freedom in 1855, less than a year after his recapture.

The fight against the Fugitive Slave Act in Boston didn’t stop there. In 1855, the same year Burns regained his freedom, Massachusetts passed the Massachusetts Personal Liberty Act10, a state law that just did not encourage non-cooperation of the Fugitive Slave Act, but defied it at every step. The law demanded escaped enslaved persons be given Habeus Corpus, that any state officers were forbidden from assisting in the execution of the unjust warrants of the Fugitive Slave Act, and that those private citizens that assisted in the recapture of those emancipated persons, be fined $5000.

This wasn’t just an ignoring of federal law, it was defiance; and Massachusetts wasn’t the only state to fight back against the blatant misuse of federal power. From the Supreme Court in Wisconsin, to the legislatures of Ohio and Michigan, Free states and cities all across the country flexed their muscles to to defend themselves not just against the overreach of Washington DC and the enslaver states, but to protect all the people found within their borders.11 Each city, each state, declaring themselves a sanctuary to those in chains. Such defiance could be summed up in three words.

DO NOT COMPLY

Which brings us to today. America finds itself is similar landscape to the 1850s. Whereas in 1854, Federal Law demanded that States enforce the re-enslavement of men and women, today Federal Law is being used to detain and deport immigrants across the country. Where Asa Butman and his ilk back then would eagerly hunt emancipated men and women for financial reward, we have ICE agents swarming up to stores, farms and schools, tearing apart families and shuttling people off without due process for crimes unknown. Instead of Franklin Pierce sending in troops to Boston to ensure the transfer of an unjustly chained man, we have Donald Trump sending in Marines and National Guard to Los Angeles to suppress the justified outrage of the people of that city. Where judges in Boston would issue inhumane warrants, we have courts dimissing immigration cases at the behest of Trump and his goons, so that immigrants suddenly find themselves without legal status and can be swept up in the anrachy. 12

Its the same story, playing over again.

But we also find hope. States and Cities are declaring themselves sanctuaries to immigrants, much like Boston did 170 years ago to the enslaved. Advocacy groups are bringing cases to court and winning, pushing back against Washington DC’s draconian sweeps and deportations. Governors are reclaiming their National Guard and challenging the Administration directly, in public, letting all within their borders that they will fight for them.

And we have citizens, millions of them, all across this blessed land, marching, adovcating protesting. Telling those in Washington DC that you will not will, you will lose, and that America is not for the enslaver, the bigot, the racist, it is for all people. That it doesn’t matter how many troops are sent in, or how many exucutive orders are signed, the answer, the response, will always be the same.

DO NOT COMPLY

- “Anthony Burns Captured,” PBS, accessed June 15, 2025, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2915.html. ↩︎

- “Article Four of the United States Constitution.” Wikipedia, April 30, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Article_Four_of_the_United_States_Constitution#Clause_3:_Fugitive_Slave_Clause.

↩︎ - “Fugitive Slave Act of 1793.” Wikipedia, June 6, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fugitive_Slave_Act_of_1793.

↩︎ - “Public Acts of the Thirty First Congress .” https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llsl/llsl-c31/llsl-c31.pdf?loclr=bloglaw#page=42. Accessed June 16, 2025. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llsl/llsl-c4/llsl-c4.pdf?loclr=bloglaw.

↩︎ - “Public Acts of the Thirty First Congress .” https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llsl/llsl-c31/llsl-c31.pdf?loclr=bloglaw#page=42. Accessed June 16, 2025. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llsl/llsl-c4/llsl-c4.pdf?loclr=bloglaw.

↩︎ - “Public Acts of the Thirty First Congress .” https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llsl/llsl-c31/llsl-c31.pdf?loclr=bloglaw#page=42. Accessed June 16, 2025. https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llsl/llsl-c4/llsl-c4.pdf?loclr=bloglaw.

↩︎ - “Asa O Butman Captured Fugitive in England.” Newspapers.com, May 9, 1850. https://www.newspapers.com/article/milwaukee-daily-sentinel-asa-o-butman-ca/59155202/.

↩︎ - Jennifer González, “Escaping Slavery: The Consequences of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850: In Custodia Legis,” The Library of Congress, February 8, 2023, https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2023/02/escaping-slavery-the-consquences-of-the-fugitive-slave-act-of-1850/. ↩︎

- “Leonard Grimes (U.S. National Park Service),” National Parks Service, accessed June 15, 2025, https://www.nps.gov/people/leonard-grimes.htm. ↩︎

- “Massachusetts Personal Liberty Act (1855).” National Constitution Center – constitutioncenter.org. Accessed June 15, 2025. https://constitutioncenter.org/the-constitution/historic-document-library/detail/massachusetts-personal-liberty-act-1855.

↩︎ - “Black Laws, Liberty Laws & Freedom Suits.” The African American Midwest. Accessed June 15, 2025. https://africanamericanmidwest.com/history-slavery/black-laws-liberty-laws-freedom-lawsuits/#:~:text=Indiana%20required%20blacks%20residing%20in%20the%20state,Slave%20Act%20in%20Ohio%2C%20Michigan%20and%20Wisconsin.

↩︎ - Ainsley, Julia. “Trump Admin Tells Immigration Judges to Dismiss Cases in Tactic to Speed up Arrests.” NBCNews.com, June 11, 2025. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/national-security/trump-admin-tells-immigration-judges-dismiss-cases-tactic-speed-arrest-rcna212138.

↩︎