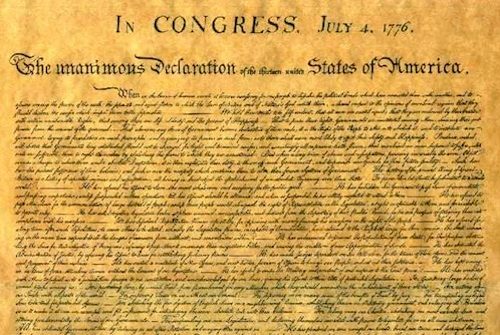

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” (5)

Self-evident. What an interesting term. When reciting this most famous portion of The Declaration of Independence, a reader can be forgiven for skipping over the “self-evident” to get to the meatier fare or Life, Liberty and pursuit of Happiness. After all, self-evident is, self-evident of course! To borrow the cliche, self-evident “is what it is.” It needs no explanation, no proofs, no eloquent poetry to lofty prose to make its case for it. It stands on its own as it should. And what is more self-evident than what Jefferson said when he declared before the world that all men were created equal.

The concept of this self-evident liberty is embedded in the very foundation of our American Mythology. Americans, if nothing else, are free. We have our liberties. Our rights. Rights that stem from the seed of the Declaration and take full bloom within the structure of our Constitution. Any issue, be it political, economic, or diplomatic, always must pass the first litmus test of “but how will it affect my freedoms?” Americans are loath to sacrifice any of their perceived liberty. To instinctively distrust any sort of government entitlement or tax as an assault on the liberties that we all hold so dear. For what is the blood and sacrifice of all those who died to ensure our liberty if we meekly give it away for the sake of the soft tyranny known as “security”? It was for liberty that patriots fought and defeated the British in the Revolutionary War, and again in 1812. It was for the life of the nation that the Union defeated the Confederates in 1865, receiving their surrender in a small courthouse in Appomattox. It was for the pursuit of happiness that pioneers set out westward in the 1800s. In the 1940s, American blood bought all three for the world over on the shores of France and the islands of the Pacific.

Life liberty and the pursuit of happiness are not just an American slogan, they are our defining character trait. They are also a trait that reflects the character of their author, Thomas Jefferson.

To say Thomas Jefferson was an important character in American history would be an understatement of continental proportions. If Washington was the founder that won America’s independence, Jefferson was the founder that wrote the fledgling nation into existence. It is his words and deeds that shaped the foundation, function and structure of our nation to a greater extent than any other single person. To understand America is to understand Jefferson. That much should be self-evident.

To understand Jefferson is an undertaking that will be both rewarding and demoralizing. Both inspiring and infuriating. For Thomas Jefferson was a man who ascended the greatest heights of human intellect. According to Stephen Ambrose “Jefferson’s range of knowledge was astonishing. Science in general. Flora and fauna specifically. Geography. Fossils. The classics and modern literature. Languages. Politicians of all types. Politics, state by state, county by county. International affairs. He was an intense partisan. He loved music and playing the violin. He wrote countless letters about his philosophy, observations of people and places. In his official correspondence, Jefferson maintained a level of eloquence not since equaled.” (1) He was a walking embodiment of enlightenment and reason. Whatever virtues people like to ascribe to our founders, Thomas Jefferson marked every single one of them. In him, we can see America at her best.

Which makes it all the sadder that in him we also see America at her worst.

It is a universally known fact that Thomas Jefferson was a slave owner. This is not a surprise as most, if not all, of the founders had enslaved people at one point or another. Nine presidents held people in bondage, including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Like many, Jefferson inherited his first enslaved people from his father, and was expected to run his plantations. Like many, Jefferson’s enslaved were expected to work under extreme conditions, with barely enough food, shelter and clothing to survive. Like many, Jefferson would have the enslaved whipped when they failed to keep up with his work quotas. Like many, Jefferson was just a product of his time.

Or so some would have us believe.

A “product of their time” is the comforting blanket of excuses people use when they are unable to confront the ugly, self-evident truths of historical figures they have been told to revere. It allows us to forgive the sins of our historical heroes so as to not crack the facade of our collective mythology. It demands we engage in an exercise of willful ignorance that will only succeed in hamstringing our ability to think critically of our past and to be able to use that knowledge constructively to build our future.

To those that declare we must treat any historical review of Jefferson as him merely being a product of his time, we must respond by challenging the premise of that statement. Was he? Was Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration, founding father, president of the United States, merely just a vessel blown by the winds of circumstance and fate, destined to be nothing more than a product of his time?

To answer this question, let us start with the most glaring example of cognitive dissonance, that of the fact that Jefferson was an owner of enslaved people. He was not just any slaver, either. Over his lifetime Thomas Jefferson owned over 600 slaves and ran one of the largest plantations in the state of Virginia. That alone should put to rest any notion that he was some sort of American saint and as such above reproach. But many will again rightly point out, many founders owned slaves. How can we as a society judge so harshly Jefferson and his misdeeds and give a pass to the other founders, Washington foremost among them?

Which is a fair question, why does Washington get a more favorable treatment by history? Is it just because he was the Founding Father where the others were just were secondary founders? Washington held enslaved people. He had them whipped when they would “not do their duty by fair means, or are impertinent.” (13) “Washington also relentlessly pursued escaped slaves and circumvented laws that would allow his enslaved workers freedom if they did manage to escape to neighboring states.” (13) Washington, by most measures, was just as guilty as Jefferson in his perpetuation of America’s original sin.

However, there are three things that grant Washington a measure of absolution that we should not extend to Jefferson. The first is that George Washington did free his enslaved. To be true, he only did so in his will and only upon his wife Martha’s death or consent. And of 317 enslaved people on Mount Vernon at the time of his death, only 123 were eligible to be freed as the rest came from his wife’s estate to which they reverted back when Washington died. Even so, in January, 1801, 123 men and women who had been in bondage their whole life, were able to leave Mount Vernon, free. (3)

There is another issue that separates Washington and Jefferson, is their personal character and how it changed over their lifetimes. Washington inherited his first enslaved persons at age 11 when his father passed away. After that he grew his estate and his number of enslaved throughout his life. He grew up in a society that did not merely allow the slavery of black people but was structured around it. “Everything around young Washington would have reinforced the concept that God and society saw slavery as something which was only right and natural. His parents and neighbors owned enslaved people…By the time of Washington’s birth, slavery had been a fact of Virginia life for almost a century and was a seemingly indispensable part of the economic, social, legal, and political fabric of the colony.” (15) To Washington, slavery was not something that just happened, it was a way of life, one which he zealously engaged in. He was a demanding plantation owner, doling out punishment, black or white, to those that let him down while at the same time showing favor to those that met his exacting standards. (15)

But something changed in George Washington over the course of his life, something that we see as a man who was wrestling with his own place in this system that existed by subjugating one for the benefit of another. In 1778,in the midst of the Revolutionary War, he stated he wished “to get quit of negroes.” (17) By 1786, Washington made a pledge to never purchase another person and for the hope of abolition of slavery in America outright. “I never mean (unless some particular circumstance should compel me to it) to possess another slave by purchase: it being among my first wishes to see some plan adopted by the legislature by which slavery in the Country may be abolished by slow, sure, & imperceptible degrees.” (16)

What changed? How did a man who at one point thought a system of slavery was not only acceptable, but also right, become a man who wished for the total abolition of the system and who emancipated his own bondsmen upon his death? Likely, as with all things, the reasons are both many and at the same time singular. Washington was a very intelligent man and could see on purely economic reasons that owning and keeping enslaved people was financially unsustainable as it cost more to feed, house and clothe slaves than it would to just pay freemen to work the fields. He said as much in 1799. (16)

Washington also likely could not harmonize the moral and mental conflict of fighting for the birth of a nation based upon liberty and equality that also kept an entire demographic of people either in bondage or as second class citizens, especially when the ranks of his very own Continental Army was comprised of 5,000 free and enslaved black soldiers. Or possibly it was in 1775 when Philiss Wheatly, a young black enslaved woman sent Washington a poem praising his leadership to which he responded praising her talent and invited her to meet him. (17) More likely is that it was a confluence of these and other events throughout his life that transformed Washington from ardent slave owner into a posthumous emancipator.

Which brings us to the third reason Washington is treated more favorably in the eyes of history. The previous paragraph is a multitude of ways of saying the same thing. An avalanche of evidence crashing upon Washington’s own conscience. Because all of those reasons and circumstances point to the same inevitable conclusion, one that Washington reached, and although belatedly, acted upon. That slavery, in its many and insidious forms, was wrong. Irretrievably and irrevocably wrong. Any justification otherwise rang as hollow then as it does today. Because really, that is all it should come down to. If “all men are created equal” is a self-evident truth, then so must be the inverse, that any man held in bondage is an abomination, an abomination that cannot be allowed to abide in a supposedly free and equal society.

This perhaps, is why Washington receives some measure of absolution. Not enough to pretend that what was true was not or that he was some semi-divine figure who could do no wrong. Not at all. His wrongs were legion and he needs to be held to account for them in the grand scope of history. But he also needs to be recognized as one, at least in this regard, as not merely a product of his time. As one who strove to make at least in some small part, right what he had made wrong. That, though incomplete as it was, is commendable.

Which brings us back to Jefferson. You didn’t think he had been forgotten, had you? What makes Thomas Jefferson so interesting is that his life is almost an inverse trajectory of that of George Washington’s. Where Washington ardently supported slavery in his younger years, Jefferson was one of the early founders who called for abolition of slavery. “‘One cannot question the genuineness of Jefferson’s liberal dreams,’ writes historian David Brion Davis. ‘He was one of the first statesmen in any part of the world to advocate concrete measures for restricting and eradicating Negro slavery.’” (17)

Jefferson frequently called for the abolition of slavery throughout Virginia and in the nation as a whole. “At the time of the American Revolution, Jefferson was actively involved in legislation that he hoped would result in slavery’s abolition. In 1778, he drafted a Virginia law that prohibited the importation of enslaved Africans. In 1784, he proposed an ordinance that would ban slavery in the Northwest territories.”(11) Jefferson believed in a gradual emancipation that slave owners would have to agree to of their own free will that would be consistent with his republican ideals. He also thought that by banning the transatlantic slave trade that slavery would die out in America of its own accord since the source of slaves would be shut off.

But this idea is based on the naivety that an evil will give up its hold easily. If the plantation owners and farmers were unable to buy slaves directly from Africa, then they would just make their own. The transatlantic slave trade was banned in America in 1807 and yet the number of slaves continued to grow. By 1830 there were 469,757 slaves in Virginia alone. Farmers and and Plantation owners realized with a cruel efficiency that instead or tobacco or cotton, the slaves them selves would be their cash crop.

This was a realization that Jefferson himself had, one that he turned into opportunity. Whereas Washington saw losses in the upkeep of owning enslaved persons, Jefferson saw annual profits. “What Jefferson set out clearly for the first time was that he was making a 4 percent profit every year on the birth of black children. The enslaved were yielding him a bonanza, a perpetual human dividend at compound interest. Jefferson wrote, ‘I allow nothing for losses by death, but, on the contrary, shall presently take credit four per cent. per annum, for their increase over and above keeping up their own numbers.’ His plantation was producing inexhaustible human assets. The percentage was predictable.” (17)

This economic epiphany may very well have shifted Jefferson’s perspective from that of the would-be emancipator of the 1770s into the miserly slaver of the 1790’s. Keep in mind that Jefferson was an owner of the enslaved throughout his life, like Washington was. What is so tragically fascinating is his perspective shift in comparison to Washington’s. Whereas Washington seems to have struggled more and more throughout his life with the idea of chattel slavery, Jefferson was somehow able to rationalize his public persona as egalitarian while at the same time ruthlessly squeeze his own slaves for every penny he could.

And he was ruthless. Once he realized he could industrialize his slaves to maximum efficiency, he wasted no time in executing those plans. One of the most salient examples of this was the nail factory Jefferson had at Monticello. “He launched the nailery in 1794 and supervised it personally for three years. ‘I now employ a dozen little boys from 10. to 16. years of age, overlooking all the details of their business myself.’” (17) By 1796, the nailery was producing from 5,000 to 10,000 nails a day, producing enough money to cover the grocery bill of the estate for the year. The nailery became so important to the operations in Monticello, that if the young boys working in it failed to meet quotas, they were often whipped to get them back to work.

These harsh conditions bred resentment among the workers, as failure to meet quotas would lead to punishment, often being relegated to the whip or being sent back into the fields where they received less food and poor clothing. This resentment and fear of punishment lead to a dangerous hierarchy among the slaves in the nailery, exploding to violence when “In 1803 a nailer named Cary smashed his hammer into the skull of a fellow nailer, Brown Colbert.” (17) Colbert had hidden Cary’s nail rod, knowing that if he could not find it, he would fall behind the others and be whipped by the cruel overseer Gabriel Lilly.

A thousand examples of abuse and deprivation have been found in Jefferson’s Monticello. For all that he presented himself to the world as this American ideal of virtue and mercy, he was at his heart, a slaver. A man who saw the economic advantages as more important than the lives and liberties of those he held in bondage. He justified his actions by curating the image of a benevolent master, a man who said “I love industry and abhor severity” (17) as a way of presenting himself as something he was not. Whereas Washington was ruthless and severe, Jefferson was a coward, trying to show people that he wasn’t the villain, that he tried to be a benevolent master, all the while bemoaning the fact that he had to beat children to get back to work.

He carried these rationalizations further, using his enlightened mind to explain how in reality Black people were less intelligent and less capable than their white counterparts. Nevermind that his entire operation was dependent upon a “retrained work force of millers, mechanics, carpenters, smiths, spinners, coopers, and plowmen;” (17) all Black men and women. What is so fascinating about Jefferson, is as one reads his words, they will see on one end a man who will rightly call out the inhumanity of the African slave trade and the subjugation of the Native peoples of the Americas while at the same time bemoaning that some of his own slaves “‘would never readily submit to bondage.’ Some, Jefferson wrote, ‘require a vigour of discipline to make them do reasonable work.’” (17)

Many will again point out that Jefferson did push for the emancipation of slaves in America. Which is true! Jefferson did wish to “emancipate all slaves born after passing the act,” (10) the act being a bill presented as an amendment to the Continental Congress. It cannot be overstated how frequently Jefferson called for the freedom of slaves in America.

But these calls for freedom of the enslaved beg some questions, the first one being what sort of freedom did Jefferson envision for the newly liberated? Was it a pure vision of a fully integrated America, where men and women of all races, color and background would be able to fully partake in the blessings of liberty and prosperity? By now, one should know that was not the case.

Jefferson instead argued that emancipated Black men and women “should be colonized to such place as the circumstances of the time should render most proper, sending them out with arms, implements of houshold and of the handicraft arts, feeds, pairs of the useful domestic animals, &c. to declare them a free and independant people, and extend to them our alliance and protection, till they shall have acquired strength; and to send vessels at the same time to other parts of the world for an equal number of white inhabitants; to induce whom to migrate hither, proper encouragements were to be proposed.” (10)

If any were confused by the above passage, let that confusion be dispelled right now. Jefferson was advocating for sending the freed men and women back to Africa and in turn bringing an equal number of white folks to America from various places around the world. Jefferson did not want an integrated America at all, instead he wanted a white America with Black folks completely segregated in their own nation back in Africa.

On the surface, this does not look like the worst solution. After all, wouldn’t being free in Africa be better than being enslaved in America? Absolutely, but that does not mean that is the right course. The thing that Jefferson and people like him who supported this “back to Africa” ideology failed to realize is that if every slave was suddenly freed and sent back they would be strangers in a strange land. The first Africans came to America in 1619. Since that first arrival, the population of enslaved in America exploded. By 1781, there were around 575,000 slaves in America. Jefferson himself calculated that in Virginia alone in 1782, there were 270,762 enslaved compared to 206,852 free inhabitants. Many of those people in bondage, were not brought over on ships from Africa, but were born in America. They were descendants of people who were ripped from their homes, stripped of their identity and history, forced to worship a foreign god, and made to speak an unfamiliar language while at the same time not being allowed to read it. Those enslaved people, whether they wanted to or not, and whether their white owners were willing to admit it, were born, beaten, and buried as Americans. Africa was even more foreign to them as Germany would be to me. They no longer had any ties to that land beyond sharing skin color. The slavers and their enablers, people like Jefferson and Washington had made sure of it.

Sending them back to a land where all connection was intentionally destroyed and erased would be almost as cruel as keeping them in bondage of the country they were born in.

There is an even more insidious problem with Jefferson’s proposed emancipation of the enslaved, and that comes down to a simple question of why? Why did Jefferson think this was a better solution than keeping the newly freed here and integrated in America. How fortunate it is for us that Jefferson rhetorically asked and answered this very question. In his Notes on the State of Virginia, Jefferson posed the question of why emancipation and relocation was a better solution to the issue of slavery than that of emancipation and integration. His reasons were vast and varied from the understanding of “Deep rooted prejudices entertained by the whites; ten thousand recollections, by the blacks, of the injuries they have sustained” (10), which was a very real consequence of emancipation. Prejudices of white people towards Black, and their remembrances of the innumerable injustices they faced at the hands of white people have left deep, unhealed wounds that continue to fester to this day in America.

Does this mean because these wounds do exist, that Jefferson was right and everyone would have been better off if the newly freed were just sent back to Africa? Not at all! In fact this was tried during from 1822 – 1861, where free blacks volunteered to repatriate back to Africa through the American Colonization Society (ACS) and setting up the country of Liberia. The ACS was largely organized and motivated by two main groups, Quakers and slaveholders. The Quakers, some of America’s first and most ardent abolitionists, feared that free Black people would never be able to enjoy as much freedom in America as they would back in Africa. President Lincoln was an ardent supporter of the ACS, believing the same. The slaveholders on the other hand, largely did not support emancipation but believed that if there were to be free Blacks, it would be better if they were at least back in Africa and not in America, where their mere presence would cause possible unrest amongst their own enslaved.

Whether the repatriation movement was a success would depend on one’s definition of what they mean by success. Yes, the United states successfully repatriated around 15,000 free Black men and women to Liberia. During that time those free Blacks did successfully establish a colony, declare and receive independence from the United States, and go on to become Africa’s oldest modern republic. But that success must be tempered with the realization that Liberia also went on to become a highly stratified society, where an elite few, those Americo-Liberian colonists sat at the top and the indigenous peoples who they shared no cultural identity with beyond skin color were marginalized and persecuted.

But it was not just the prejudices of whites and the recollection of Blacks that Jefferson stated as reasons for the incompatibility to emancipate and incorporate Black people fully into American society. In fact, some of his reasons were simply base and cruel at their heart, though Jefferson covered them in the satin cloth of his own eloquence. He stated that the “difference is fixed in nature…and is this difference of no importance? Is it not the foundation of a greater or less share of beauty in the two races?” (10) He continued by saying being white was preferable to the “eternal monotony” of being Black, and that white people with their “flowing hair, a more elegant symmetry of form” (10) were so beautiful that even Black men and women found white people more attractive. He continues with this reasoning by stating that Black people have “ a very strong and disagreeable odour…a want of forethought… their existence appears to participate more of sensation than reflection…in memory they are equal to the whites; in reason much inferior, as I think one could scarcely be found capable of tracing and comprehending the investigations of Euclid; and that in imagination they are dull, tasteless, and anomalous.” (10)

Do you need to read that again? Did you pick up on the theme he presented? Does Jefferson appears concerned for the well being of his fellow man, one he wants to see treated equally and thrive as much as his white brethren? No! Thomas Jefferson’s concern for the Black men of women in America only went so far as what to do with a favored workhorse when it is no longer useful. If Black people are to be free, in Jefferson’s mind, then their value to him specifically and to America at large is over. Better to replace them with white workers, because as he so clearly stated, the Black people not only were less beautiful, and smelled worse than a white counterpart, they were prone to sleeping, incapable of reason, forethought, and lacked imagination.

Which brings me to another point. Do those reasons sound familiar? Do they strike you with a sense of deja vu? Because to me, this almost sounds verbatim the same rationale used by the racist of today when they will loudly and unsolicitedly declare the “reason” that Black Americans are struggling today in a society that has been setup to work against them. The genteel racism of many in America today will claim Black unemployment is high because they are lazy, or that Black people are incapable of producing “real” music, or writing the next great American novel because they lack imagination, or are incapable of having the foresight and intellect to be in positions of leadership. It’s as if Thomas Jefferson created a primer for the racism of modern day America, a playbook for the lazy bigots that surround us to use in a pinch without having to critically assess the merits, or lack thereof, of the auditory vomit of their mouths. If they are confronted with the fact that the lies they perpetuate, are figments of a racist plantation owner who happened to be a founder of the United States, they will declare that you are trying to “erase history” or “destroy America,” as if America would somehow collapse if the cult of the founding fathers was finally torn down.

What’s worse, is that Jefferson was routinely confronted with the reality that what he was saying about Black people was as false as the illusion of the “good slave owner” itself. For one, Jefferson’s declarations that whites and Blacks respectively have a “greater and less share of beauty,” fall flat when the subject of his own non-consenual affair and the children he fathered with his slave Sally Hemings. A fact that is so often glossed over, and is so worse when one realizes that many of the Hemings going back generations, not just Sally, were frequently used as sex slaves for those on Monticello. (4)

Adding to that, Jefferson’s belief in the intellectual inferiority of Black people was not only entirely incorrect, but was singlehandedly rebutted in the person of Benjamin Banneker. Banneker was born a free Black man in Baltimore in 1731. Growing up free, Banneker was able to pursue his intellectual interests, becoming a renowned inventor, astronomer, and author. He went on to assist Andrew Ellicott in the original surveys of Washington DC in 1791. However, what he is most famous for, and what connects him to Jefferson, were his almanacs. Banneker created annual almanacs, using his expertise in astronomy that accurately predicted eclipses, and conjunctions of planetary bodies each year. During the year 1791, Banneker sent a letter to Thomas Jefferson with his almanac for the next year included. In that letter, is perhaps the single greatest response to Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence that almost no one has ever heard of. In it, Banneker does what we all should do. He calls on Jefferson to live up to the high ideals Jefferson wrote in the Declaration of Independence and shining the light of truth on Jefferson’s hypocrisy, stating “Sir how pitiable is it to reflect, that altho you were so fully convinced of the benevolence of the Father of mankind, and of his equal and impartial distribution of those rights and privileges which he had conferred upon them, that you should at the Same time counteract his mercies, in detaining by fraud and violence so numerous a part of my brethren under groaning captivity and cruel oppression.” (2) Banneker goes on to ask Jefferson “to wean yourselves from these narrow prejudices which you have imbibed with respect to them, and as Job proposed to his friends ‘Put your Souls in their Souls stead,’ thus shall your hearts be enlarged with kindness and benevolence toward them, and thus shall you need neither the direction of myself or others in what manner to proceed herein.” (2)

The entirety of the letter that Banneker wrote to Jefferson is the perfect companion piece to the Declaration of Independence. Whereas the Declaration proclaims ideals upon which all men should strive to live up to, the Letter highlights how far we fall short of those ideals and how we need someone to tell us to remove the plank from our own eyes if we are to truly see clearly. For every Jefferson, the world needs a Banneker. One who is not afraid to speak the truth to those in places of power, consequences be damned. Banneker is to Jefferson what the prophet Nathan was to King David, confronting the man directly with his own sin. And though Jefferson did respond to Banneker, thanking him for his correspondence and saying “No body wishes more than I do to see such proofs as you exhibit, that nature has given to our black brethren, talents equal to those of the other colours of men,” (8) and “wishes more ardently to see a good system commenced for raising the condition both of their body and mind to what it ought to be,” (8) Jefferson did not repent of his sin as David did. He did not suddenly emancipate his own enslaved people and become the ardent abolitionist that some whitewashed version of American history wishes he did.

Instead, he continued to seek “more proofs” that Black men and women were in fact just as smart, imaginative, and beautiful as their white counterparts. He “wished” more than anybody that these proofs would become evident, or so he says. But here’s the thing, the more one reads, the more one sees either his wishes for these proofs were either halfhearted at best, or that he never wanted to see the truth. Which is odd, because how could he avoid it? Banneker was quietly literally knocking down the lies of Black inferiority in his mere existence. Banneker was just as educated as Jefferson, just as intelligent, just as eloquent. What more proof did the Founder need?

You see, that’s the biggest problem with Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson knew. He knew that “that one universal Father hath given being to us all, and that he hath not only made us all of one flesh, but that he hath also without partiality afforded us all the Same Sensations…we are all of the Same Family, and Stand in the Same relation to him.” (2) He knew that the fabrications he spun of intellectual and physical inferiority were just that, fabrications. For if they weren’t fabrications and he actually believed what he said, why would he continually indenture Black men and women to be his laborers, artisans and craftsmen when he could have the supposedly superior white men and women work in his fields?

The reason he told himself and others these comforting lies, is that because he knew the enslaved people he held were endowed by their creator just as equally as he was, he also knew that he was denying them their god given rights. So, instead of confronting that reality, that truth, he held onto the lie, and created well spoken but spurious academic arguments for the continued bondage of his fellow man.

But why? Why cling to the owning and keeping of enslaved people throughout his life and into his death? He knew it was wrong. He said as much many times over. Jefferson was even given the opportunity to free his own enslaved people. On a silver platter, he was given a chance to free all those held in bondage at Monticello, thanks to a man named Thaddeus Kosciuszko, a man who was a lifelong friend of Jefferson’s dating back to the Revolutionary War. When Kosciuszko died in 1817, he “bequeathed funds to free Jefferson’s slaves and purchase land and farming equipment for them to begin a life on their own,” (17) saying “’I hereby authorize my friend, Thomas Jefferson, to employ the whole [bequest] in purchasing Negroes from his own or any others and giving them liberty in my name.’” (17) And what did Jefferson do with this bequest for emancipation from his friend? He turned it down. Why? It would have reduced the chronic debt that Jefferson carried throughout his life. Freeing his enslaved also would have removed the hypocrisy he was living in by declaring all equal and yet depriving equality from many. It would have been the morally right thing to do. Again, I ask, why?

Because he was an addict. When deciding whether or not to accept the bequest, Jefferson “had written to one of his plantation managers: ‘A child raised every 2. years is of more profit then the crop of the best laboring man. in this, as in all other cases, providence has made our duties and our interests coincide perfectly…. [W]ith respect therefore to our women & their children I must pray you to inculcate upon the overseers that it is not their labor, but their increase which is the first consideration with us.’” (17)

Jefferson couldn’t kick the habit. He couldn’t give up the addiction that is slavery. The owning of people became an economic high for him. He delighted in counting how much money he made just from having slaves, totally detached from the work his slaves produced.

I will say it again. Jefferson knew. He knew, and he didn’t care. Not only did he not care, he wrote powerful prose about the evils of slavery and the virtues of equality of all men, professing to care, pulling the wool over our collective eyes. Which is what makes it all the worse. Many of the founders owned slaves as did most of our earliest presidents. That was not unusual. Conversely, many in America were abolitionists, though their reasons often varied. Again, not unusual for the time. But only Jefferson was someone who professed the emancipation of slaves while at the time time clenching his fist ever tighter to his own. He is the only one who made sure, lofty declarations for the American ideal while in reality embodying its exact opposite.

Thomas Jefferson wasn’t a product of his time. That excuse flew out the window the moment he penned the words “We hold these truths.” Jefferson wasn’t a product of his time, the time was a product of him. He, among a select few others, was shaping the world in his hands, forming it and setting it in motion for generations to come. Jefferson, more than almost anybody, could have set the young United States down a much different path. A path that would have been more just, more equal, more free, for all people. He had his hands on the levers of liberty, and he did nothing. He had a chance to rise to his own proclaimed highest ideal for American virtue, and instead he failed to meet even the most basic of those standards. Jefferson knew. He knew and he didn’t care. He didn’t care and millions suffered.

What is so sad is that while this is all painfully self evident, so many in America today, like Jefferson, will clothe themselves in the same comforting lies that he did. They will hide their faces from the truth that stares them in the face, will say the right things but fail to live up to their own words. That so many have deluded themselves into believing we are something that we are not. That we are more equal, free, and just than we really are. That because we said that all men are created equal, we do not have to live by those words as the mere speaking of them is enough.

That we still look to Jefferson as some American ideal when we have Banneker staring us in the face, begging us to rise above our base selves, to live the virtues we proclaim to have, while we pointedly ignore him, is not only the greatest indictment we can bring upon ourselves, but also the most avoidable. The only more self-evident than Jefferson’s failures as a man who could not or would not live up to his own words, is our willful ignorance to that truth.

Bibliography

- 1)Ambrose, Stephen. “Founding Fathers and Slaveholders.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, November 1, 2002. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/founding-fathers-and-slaveholders-72262393/.

- 2)Banneker, Benjamin. “Founders Online: To Thomas Jefferson from Benjamin Banneker, 19 August 1791.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-22-02-0049.

- 3)Blakemore, Erin. “Did George Washington Really Free Mount Vernon’s Enslaved Workers?” History.com. A&E Television Networks, October 11, 2017. https://www.history.com/news/did-george-washington-really-free-mount-vernons-slaves.

- 4)“Sally Hemings: Life of Sally Hemings.” Sally Hemings | Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello. Monticello. Accessed January 9, 2022. https://www.monticello.org/sallyhemings/.

- 5)Jefferson, Thomas, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert R Livingston. “Declaration of Independence: A Transcription.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration, October 7, 2021. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript.

- 6)Jefferson, Thomas. “Autobiography.” Avalon Project – Jefferson’s autobiography. The Avalon Project: Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library, 2008. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/jeffauto.asp.

- 7)Jefferson, Thomas. “Draft Constitution for Virginia 1776.” Avalon Project – Draft CCONSTITUTION for Virginia 1776. The Avalon Project: Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library, 2008. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/jeffcons.asp.

- 8)Jefferson, Thomas. “Founders Online: From Thomas Jefferson to Benjamin Banneker, 30 August 1791.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-22-02-0091.

- 9)Jefferson, Thomas. “Founders Online: From Thomas Jefferson to Condorcet, 30 August 1791.” National Archives and Records Administration. National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-22-02-0092.

- 10)Jefferson, Thomas. “Notes on the State of Virginia.” Avalon Project – notes on the State of Virginia. The Avalon Project: Yale Law School Lillian Goldman Law Library, 2008. https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/jeffvir.asp.

- 11)“Jefferson’s Attitudes toward Slavery.” Monticello. Monitcello. Accessed January 2, 2022. https://www.monticello.org/thomas-jefferson/jefferson-slavery/jefferson-s-attitudes-toward-slavery/.

- 12)Johnson, Samuel. “Taxation No Tyranny – 1775.” Taxation no tyranny – Samuel Johnson. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://www.samueljohnson.com/tnt.html.

- 13)“Slave Control.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, 2022. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/slave-control/.

- 14)Stanton, Lucia C. “The Slaves’ Story – Jefferson’s ‘Family’ | Jefferson’s Blood | Frontline.” Frontline. Public Broadcasting Service. Accessed January 1, 2022. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/jefferson/slaves/stanton.html.

- 15)Thompson, Mary V. “‘The Only Unavoidable Subject of Regret.’” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Accessed January 2, 2022. https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/slavery/the-only-unavoidable-subject-of-regret/.

- 16)“Washington’s Changing Views on Slavery.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. George Washington’s Mount Vernon. Accessed January 2, 2022. https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/slavery/washingtons-changing-views-on-slavery/.

- 17)Wieneck, Henry. “The Dark Side of Thomas Jefferson.” Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, October 1, 2012. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-dark-side-of-thomas-jefferson-35976004/.